Besides the chapel, West Hall contained a lecture room, a library, and studies and sleeping rooms which could accommodate about seventy students, two to the room. Occupants were permitted to paint the walls of their rooms if they wished and furniture from the “stone building on the plain,” which groups and individuals had provided, was transferred to chambers in the new building bearing the names the donors had specified for those in the old one. Since lack of furniture made it possible at first to use less than half of the sleeping rooms, appeals went out for contributions of beds, bedding and other equipment. Outfitting quarters for students cost $50.00.

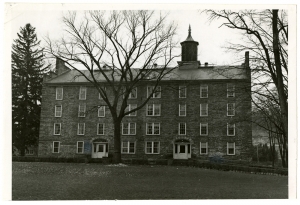

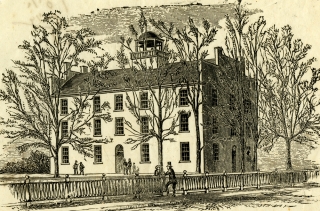

Extensive renovations have obliterated all traces of the original interior but externally the building is the same as it was in 1827. One observer then wrote that the structure was plain, well designed and constructed, and showed marks of strict economy. Today architects still comment on its simplicity and excellent proportions. In the general exterior design it resembles other college buildings of the period including Painter Hall at Middlebury, Hascall’s Alma Mater.*

Within a week after West Hall was dedicated, Hascall had completed, at a cost of $950, a “large convenient” boarding house, known as the “Cottage Edifice,” and a wood house; both were, of course, necessary complements to the new classroom and dormitory building. The boarding house, which stood between West and the present Alumni Halls, was 48 feet long and 34 feet wide and two stories high. The cellar and kitchen were in the first story, the dining room and living quarters for the steward and his family in the second.

The campus of the 1820’s and 30’s probably was bleak, bare of trees or shrubs, and without landscaping to enhance the natural beauty of the site. A new road down to the present College Street was opened and about ten acres to the north stretching to that highway were purchased. Hascall, acting as superintendent of buildings and grounds, cleared the space around the buildings and enclosed it with a fence. He also removed to the rear of the boarding house an old distillery, presumably once operated by Samuel Payne, for the students to use as a workshop. By 1829 Kendrick could report that the Education Society owned real estate worth over $12,000.

Hascall, Kendrick, and other faculty members to a lesser degree,

* The Trustees of the Hamilton Academy purchased the “building on the plain” for their boys’ department which occupied it until the academy was discontinued in the 1850’s. Hamilton Academy Record Book, Apr. 28, 1827.