teaching he occupied the pulpit in the village Baptist Church. Following his transfer from languages to theology in 1835, he went to Germany to study at Halle, Leipzig, and Berlin. Less than a year after his return in 1835 he resigned to join the Newton Faculty. Professors, students and townspeople greatly regretted his leaving. He subsequently became President of Newton, Horace Mann’s successor as Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, President of Brown, and the first General Agent of the Peabody Fund.

Another young faculty member destined to make a prominent place for himself was Asahel C. Kendrick who succeeded Sears as Professor of Languages. The son of the Rev. Clark Kendrick of Vermont, he had come to Hamilton at the age of thirteen to live with his father’s cousin, Nathaniel, while he prepared for Hamilton College at the Academy. On his graduation from Hamilton in 1831, he became an instructor in the preparatory department of the Institution. After two decades of able teaching he was to continue his career at the University of Rochester.

For a few years in the 1820’s the Executive Committee hired upperclassmen and recent graduates as tutors to assist with the instruction of beginning students. Beriah N. Leach, Class of 1825, was employed while a senior with the understanding that he should have “sabbaths to himself, and … the privilege of attending the theological lectures….” When he left at the end of a year to take a pastorate, his classmate, Chancellor Hartshorn, succeeded him but after a two-year

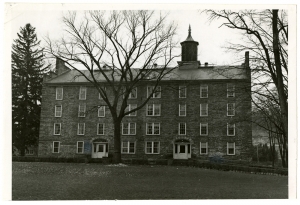

As the Trustees reviewed the progress of the Institution to 1833, they took courage from the evidence they found that it “had been raised up by special providence of God, amidst the prayers and efforts of his people.” They could point to a widening patronage from churches and friends, an able and self-sacrificing faculty, an extensive campus and substantial buildings, and a growing student enrollment. The latter called for new facilities, and an expanded curriculum, which the Board was prepared to provide in the expectation that increased contributions to the treasury would cover the cost. Both the Trustees and Executive Committee could agree that the Institution had become “too important to the interests of Zion to be neglected and left to wither.”*

* Baptist Education Society, Annual Report, 1833, pp.3, 11.