worked by the students.” Within a month, on March 15, 1826, they

bought from Payne and his wife, Betsey, their farm of 123 acres for

$2,000, half of its estimated valuation.

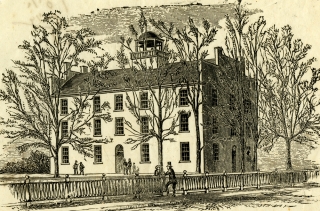

The acquisition of this property provided the Institution with a

beautiful site on a bench, or level spot, halfway up a hillside which

faced north. From this spot sweeping views, extend east, north and

west and embrace parts of the four valleys which join together at

the village below. The “Hill” with its glorious vistas of rolling fields

and woods thus became the nucleus of the Colgate campus and

quickly began to win the affections of the students of the 1820’s, a

conquest it has been repeating with their successors every year since.

The Trustees agreed to pay for the farm in six annual installments,

the last one due in 1832. In addition to a mortgage on the property,

they gave the Paynes as collateral security a bond covering three

pieces of real estate in the village and granted the use of nearly half of

the farm from which they could get a living. There is no certainty that

the $2,000 in cash was ever paid in full. Casual mention of the annual

installments in the Treasurer’s reports would seem to show that they

were made only whenever the treasury had a temporary surplus. The

Paynes’ failure to insist on a minute observance of the terms of sale

must have been gratifying to the officers of the Institution as they

sought money’ to meet the steadily mounting expenses. Final settlement was made in 1840 when the Trustees agreed

to furnish annually to the said Samuel and Betsey, during their natural lives, … The following articles and privileges, Viz: The use of the house in which they now live and the garden thereto attached.

All the fruit of the orchard. Grass and hay to keep one cow and one

horse. Two qts. of milk per day while the cow is dry.(20) Twenty bushels of corn

(50) Fifty bushels of potatoes

(5) Five barrels of flour

The cutting and drawing of twenty cords of three foot wood.*

A marker which once stood on the quadrangle of the Colgate

campus perpetuated the tradition that when, in 1794, Samuel Payne

felled the first tree of the virgin forest which covered his farm, he knelt

in prayer and dedicated his acres to God. Whether the legend is true

or not there is no question that Samuel and Betsey Payne later

staunchly supported the Seminary.

* Bond given by Trustees of BES to Samuel and Betsey Payne, Mar. 7, 1840.