made him famous as a teacher. Conservative and independent in his views, once he had formulated them, he was not a man to be “persuaded otherwise,” nor did he hesitate to express his opinions, let the chips fall where they would. These, characteristics made him a formidable adversary whenever he chose to do battle. Since his position was considered second to that of Dr. Kendrick, he had hardly taken up his duties when he began to act as Chairman of the Faculty in the absence of the former.

As early as 1830, in response to student demands for instruction in science, the Executive Committee,”having long had an eye upon a brother of much promise,” selected Joel Smith Bacon as Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy. He had graduated from Hamilton College in 1826 and was then studying at Newton. It was not until 1833, however, after completing a brief period as president of Georgetown College in Kentucky, that he accepted the offer. A year later, in accordance with a previous understanding with the Board, he exchanged his chair for that of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy. After a teaching career of only four years, he resigned in 1837 to go to Massachusetts for the settling of his father-in-law’s estate. From 1843 to 1854 he was president of Columbian College.

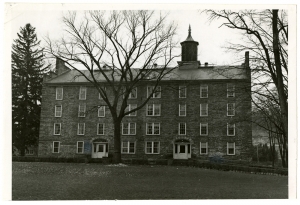

George Washington Eaton came to the faculty in the fall of 1833, probably through the influence of Bacon who wanted to be relieved of his work in mathematics and natural philosophy in order to teach intellectual and moral philosophy. As professor of Greek and Latin, Eaton had been associated with him at Georgetown College. After Bacon resigned the presidency there, Eaton, despairing of the college’s future, was glad to leave. After his appointment seemed certain, he wrote Mrs. Eaton: “I think…that this of all the places in the world is the place for us. We Can both be happy and useful here…”Thirty-eight years of devoted service bore out his initial response to the life of the Institution and village.*

A native of Pennsylvania, Eaton had grown up in Ohio where he attended Kenyon College and Ohio University at Athens. After a year’s interruption during which he was a private tutor in Virginia and studied briefly at Princeton, he resumed his education at Union College to which President Eliphalet Nott’s fame attracted him. Graduat-

*George W. Eaton to Eliza B. Eaton, Lee, Mass., Nov. 15, 1833.