organized in 1923, became Gamma Omicron of Sigma Chi in 1930 and Delta Pi Sigma, a local founded in 1928, which became Alpha Upsilon of Phi Kappa Tau in 1937. Thanks to the loyalty of alumni brothers and mortgages, nine of the original eleven fraternities constructed new houses during the period-Beta Theta Pi, 1923; Phi Gamma Delta, 1924; Theta Chi, 1926; Nu, 1927; Phi Delta Theta, 1927; Alpha Tau Omega, 1928; Lambda Chi Alpha, 1930; Kappa Delta Rho, 1930; and Delta Upsilon, 1931. The Theta Chi house has the distinction of having been the old Hamilton Female Seminary building until that school closed in 1891; it was subsequently used as a summer boarding house and in its later years stood abandoned.

Non-fraternity men had formed various loosely knit organizations to meet their social needs and had been given the use of the social room in West Hall. It was not until 1927, however, that, under the leadership of Edward M. Vinten, ’28, they succeeded in establishing a permanent group, the Colgate Commons Club. It had exclusive use of the West Hall lounge and provided fellowship and recreation for many students who could not afford fraternity membership or for other reasons had not joined the Greek letter societies.

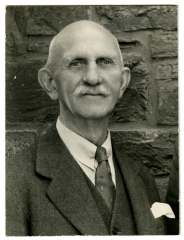

To assist the local chapters in dealing with their problems, several alumni in 1928 formed the Fraternity Alumni Council of Colgate University (Interfraternity Alumni Council) with Frank M. Williams, ’95, as president and Carlton O. Miller, ’14, as secretary. They sought through a sharing of ideas and experience to encourage scholarship among the undergraduate brothers, to assist in constructing fraternity houses and improving business practices, to bring about a more satisfactory tax policy on their real estate, to improve communication and relations among fraternity alumni, parents, faculty, administration and local residents, to aid bringing new fraternities to the campus, and to promote good fellowship among alumni of all the fraternity groups. Their work was to be most helpful.

Dissatisfaction with rushing and pledging procedures eventually led, in 1934, to an investigation by a Trustee Committee headed by William M. Parke, ’00. The committee concluded that the problem stemmed primarily from the inability of fraternities, through lack of facilities, to accommodate more than 60 percent of the student body though a great many more wanted the advantages of fraternity life. Drawing on the experience of Dartmouth they recommended that the rushing and pledging be deferred until the end of the freshman year,